haunted - Dear Mukunda Uncle,

Text Dear Mukunda Uncle, read by Sailesh Naidu.

Dear Mukunda Uncle,

I don’t remember you. That isn’t to say I do not think about you, rather it is that I have no memory of you. Nonetheless you have become an integral part of my life over the last few years. I was told you used to feed me oranges as a child. I wish taste could bring back memories like hymns do spirits. I wish when we talked your answers did not come as riddles. I wish I knew how you wanted to be remembered rather than live with a smattering of stories told by people who either knew you as kin or those who only know your name.

I saw your body once. You weren’t there. The cancer had finally taken all it could, so your spirit left. I was sixteen at the time and my mother (Rekha, Leela’s daughter. She’s doing well now, about to move to Seattle to live with her best friend) insisted my brother and I go to London for your funeral. I was mad at her. You were just an old man to me. An old man who fed me oranges once. Why did I have to leave school and cross an ocean to grieve you? I did not want to know grief, I didn’t want to know you. But mothers are wise, they have a way of living across timelines to nudge us towards futures that aren’t yet written.

Your house was cold and drabby. It was split into two levels, with two rooms downstairs, and a kitchen and living room with a faded green carpet upstairs. Avva (your sister, my grandmother) was there with Vikki Uncle. They had come to take care of you in the final months of your life. I don’t know why I am telling you all of this. You were there even though you weren’t.

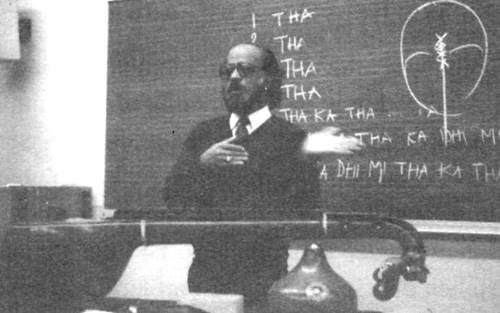

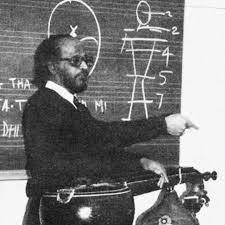

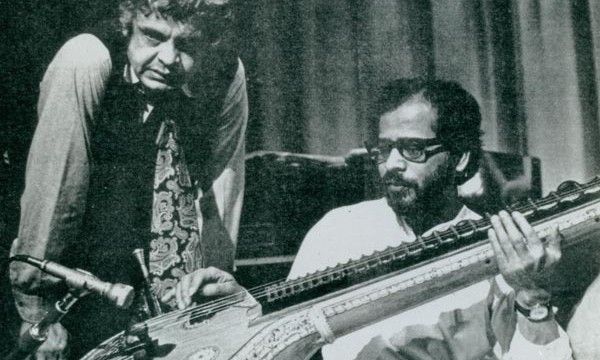

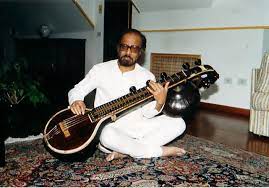

It felt strange to walk through a stranger's house. You were merely mythologies told over the dinner table and photographs that I found in drawers. You'd left India to study nuclear physics in Scotland, you’d rented a home for our family in Bangalore, you’d spent some time in Germany, you were an accomplished veena player and jazz musician, you'd created a system for using Caranatic tone and notes for sound healing. None of it made sense to me, I just wanted to go home.

The day of your funeral, your body was brought back to the house in a coffin. The family asked for it to be opened for a ritual I did not understand at the time. You were smaller than I thought you would be. I guess you had loomed so large in my imagination for so many years that I expected a giant. It was my first time seeing a dead body and I was astonished by how peaceful you were, how your container, as lifeless as it was, still anchored all of us around it. The family gathered in a tiny room around you. A Hindu priest performed a prayer and they began to sing. They sang in chants that seemed so familiar but I could barely understand them; they sang in rhythms that I knew only as nostalgia. The vibrations of their prayers filled the room and my mother took your hand. How brave it is to touch grief so tenderly and let it plant itself into something deeper, more rooted; to hold on to grief is to make the dead immortal.

We drove to your funeral in relative silence. I took in the gray streets of London for the first time. It was hard to even try to realize what your life was like there, without knowing the parts that constituted it. You became an abstraction to me, a vessel I was trying to fill with other people’s memories, just as I tried to figure out my purpose for being there. I was too young to know at the time that purpose rarely presents itself to you, rather it unfolds, inviting you in to explore.

We arrived at the church and I was astonished at how packed it was. Our family was ushered to the front. Speeches were given, I remember none of them. Hands were shaken, in a blur. After the final sermon, your coffin began to lower into the chamber below to be cremated. I looked around the abbey and saw my small Indian family amongst a sea of white faces. Who were you, I thought? Living a life so far away, so detached from what any of us really knew of you.

The funeral turned into a wake back at your house. Your friends from all over the world gathered there. There were a blur of stories from people who learned your technique in sound healing to people who knew you as a jazz musician. I saw two older men sitting in the kitchen, so my brother and I went to speak to them. They told us how they were part of a program that helped you stay in the UK after you refused to work on the Indian nuclear program. I met another friend of yours who told me how you once composed music for the famous French choreographer Maurice Béjart. I met another person who was a student of your sound healing techniques. When we die, what is left are pieces. The form can never be whole again. It is the stories that live on, the memories that endure. What is a legacy but a ghost made in someone else's image, painted in colors of how people would like to remember us. I don’t remember the rest of my trip in London. I don’t even remember coming back. I don’t remember you. It is as if this memory lived on for a purpose I wouldn’t understand till decades later. I forgot you until I couldn’t.

I had been living in Germany for 3 years before you even crossed my mind. It was in a dream. I was driving in the back of a rickshaw in India. The driver was going super fast and the cityscape was blurring around me. Suddenly, a baby elephant appeared in the road and the driver swerved to miss them. As he did, he slowed down and there you were, standing on the side of the road looking just as surprised to see me as I was to see you. I woke up with a strangeness. It was close to twenty years since your funeral, since I last thought of you, but there you were, in my dream. I had my morning coffee and sat in front of my computer and almost by instinct plugged your name into YouTube. A few videos of you popped up. But the one that stood out the most was posted exactly a month ago, in March (the month I was born.) The video was of you playing with a quartet at the Prague International Jazz Festival in 1984.

It was the first time I saw you alive, moving. It was the first time I heard your music playing. It was the first time you became real to me, not just a story. What astonished me was not only your presence as a performer but also that you had filled an auditorium of hundreds of people who had come to see you. As you played your music, the crowd sat mesmerized while being broadcasted on Czech national television. You were in every sense a rockstar on stage.

I Googled you. Over 30,000 results showed up, mostly all in German. Of all the places to find so much of you, how could it be in the country I happened to find myself in. I clicked the first link “Gesellschaft für Sonologie nach dem Nada Brahma System” ("Society for Sonology from the Nada Brahma System.”) This was your life’s work, here in German. The website explained how you had created the Nada Brahma system of sound healing. A system to help people find their ground tone or base note, and thereby developmethods of chants that would enable them to retune themselves to heal mentally and physically. Amongst photos of you playing the veena and random ohm symbols, the website detailed how your work was based on “ancient Indian traditions'' and used Samkhya philosophy. I learned that the society was started by a group of your former students to continue your work, as they quoted you "I only did the first step, you have to continue."

I clicked the “Das Sind Wir” (This Is Us) section and saw a list of all the people who have learned your technique in Germany: Andrea in Aachen, Regina Reith in Biebelsheim, Brigit in Hemsbach, Helmut in Munich, Heike in Crete, it goes on and on. Here I was thinking for years that the family had lost any connection to the work you had been doing, but I find it right under my nose in Germany, being practiced by so many people who were trained by you.

I continued my Google research to find lists of homemade websites made by older Germans speaking about your work, how they have integrated it into their healing practice and now, offering it as a service to others. Most of them credit you for the work, usually using the same copy and pasted biography and a photo of you. Some websites were super informative, others weren’t. But those that were, taught me a lot about your work, while doing little to speak about you. The system uses a 12 note Caranatic music system to identify the base frequency of each person. And through chants that you created or took from Carnatic musical text, people would be able to strengthen their own frequencies and be empowered on their own journey of self-healing.

I spent the next two years trying to track down all I can find about your life in Europe. I spoke and interviewed many of your students. I learned how you pioneered Carnatic jazz music in the West and I began to archive and digitize your music.I found archival music of you playing jazz with famous musicians like Mayard Ferguson. I found videos of you giving workshops in Germany on your sounds healing system. I tracked down your workshop books that were translated into German. I even found a video and audio cassette with your name on it in the Berlin Ethnologisches Museum (Berlin Ethnological Museum), materials that I have not been able to gain access to due to the museum not responding to any of my requests to obtain them.

There are so many ways your memory and history is alive in Germany that our family cannot fully connect to because it is in German. And it seems only through the happenstance of me ending up in Germany to learn enough German, to know where to look, that we even found remnants of your life here. Maybe you brought me here, maybe our paths were meant to intertwine, These questions are far too complex for me to answer. But the question that persists through all of this is who gets to honor your memory, who gets to define your legacy, and who gets to profit from your work.

In the interviews I undertook, many of your students held you with great honor. They spoke about how you filled halls with hundreds of people from Hamburg to Heidelberg. And even outside Germany, in the USA , Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, Austria, France, Great Britain, and Sweden. They talked about how you were a strict teacher and how short tempered you were (patience has always been lacking in our family.) What fascinated me were the biographies I found of you on the internet. Almost all of them are entirely written in German, all of those essentially the same as if copied and pasted from one another. It is as if there is a specific mythology people want to construct about you. So that an association with your image would somehow absolve them of their own past and history. That is to say purity is for the storytellers.

I wonder how you would feel that in many biographies you are referred to as Shri Vemu Mukunda. “Shri” being a title only bestowed on saints and holy leaders. Was this a title you ever consented to? Was this title given to you by another holy leader from India?

When I speak to my family about you, they are just as confused by the title of Shri as well. To us you are a brother, an uncle, a patriarch, but never a holy figure who would be held in this title. In some of your biographies, it is written that you received Brahminical education or grew up in a Brahamin (priestly) family. This also isn’t true. While our family comes from an upper caste household and has benefited from the privileges of being in that position, we have never been Brahmin. These biographies show ashocking disregard for the politics and horrors of the caste system in India that has been oppressing Dalit and Adivasi communities for thousands of years. I wonder, what notions of “purity” and legitimacy did they wish to bestow upon you with the title of “Brahmin”? I wonder if they knew the horrors that the Brahmin caste has inflicted on so many for centuries would it remind them of their own ancestors? I spoke to Leela Avva (my grandmother) and she told me how you had to learn the veena in secret and could not find a teacher because we did not belong to the right caste. And it was only after teaching yourself for years and impressing the Brahmin music teachers did they allow you to learn from them. Mythologies are strange, it is whoever tells the story that gets to make the hero what they need them to be.

The family remembers many of your students who you brought back to India to deepen their knowledge of Carnatic music. Some even post videos of you giving them accolades while in India. Others have written in your biography about how you have built a palace in India for the family to live in while you live in a small modest home in London. It’s funny having been to your house in London and also our family home in Bangalore, which you rented. I always marveled at the house being big and also being the home for four different families for your siblings. It was by no means a palace, just a big middle class home in a growing city.

I don’t see these discrepancies as inaccurate, it is more of a reflection for who gets to account your history and tell your story, and how they choose to tell it and why. I’ve learned so much about you through these accounts. For example, how you used to teach about Indian classical music in German public schools or how towards the end of your time on this plane, you had a heart attack in France and no French hospital would admit you because you were Indian, so your students had to drive you back to Freiburg in Germany.

But I have also learned a lot about you through our family. Like how as your illness progressed, the family in India would take turns flying to London to look after you and how many of them who wanted to say goodbye to you couldn’t because they were not granted a visa. Or how as your illness worsened, you became distant from your students and teachings, rarely ever speaking about them again.

I guess this brings us to how we met, when you died on February, 9 2000 and I came to your funeral. I had no idea we would meet again in so many strange and wondrous ways. How your music would become a part of my film that has played all over Germany from the Volksbühne Berlin or to theaters in Hamburg. How I would stand on the strange intersection of knowing so much about your life in India and knowing so much of your life in Germany but with no real way of bridging that gap. I see your picture hanging on walls in our family home in Bangalore and then I see your name pop up on the internet and in archives as people in Germany try to make a sound healing app based on your methodologies. I wonder who gets to really hold this part of you, the one that lives in the world so boldly. Why are the Germans the one who get to tell this story, to hold so publically your memory? Who does your legacy benefit in the end?

I also have to ask: why do the Germans need your memory to be so “pure”, priestly, and ancient? Why do other people's ancestors become their healers, their way to resolve their inner turmoil? Why do they get to hold on to these ancestral technologies and then claim it as their own? These aren’t my questions to answer.

Most of the schools started in your name began after you died. Most people who are practicing your methodologies now, have never met you. They only know you through the lens of people you taught and the stories that are told. Many of those you brought to India to meet our family,a family that showed them so much hospitality, but who have never reached out to tell them about how your legacy lives on in Germany.

I find it hard to filter your memory through the lens of whiteness. The same chants that you created based on Carnartic music that goes back for thousands of years of Indian history are now only taught by white Germans. This is hard to swallow. It is a wonder that it has been kept alive for so long, and that Europe has become a custodial caretaker of our ancestral technologies due to the horrors of coloniality.

The air here is murky, Mukunda Uncle. I can feel it every day. Germany’s past haunts every corner and its echoes can still be felt on its streets. To look at our ancestors is to acknowledge a part of ourselves. A part of me that is a bit less patient and short tempered. But what do grandparents or great-grandparents in Germany bring up for them? Why can’t they write biographies or make apps in their legacy? Why can’t they acknowledge their ghosts? These aren’t my questions to answer.

I don’t want a memory of you that is “pure”. I want to know you. The one that was flawed, the one that had a bad temper, the one that despite spending decades trying to heal other people could not heal himself. There is beauty there. There you are human. I know through my own healing journey that we never really reach an end, we just come to terms with our scars and learn to survive with our wounds. There is love there, in seeing ourselves as complicated and broken and still worthy of care.

My life is full here, Mukunda Uncle. Full of queers and weirdos and misfits and sexworkers and the unhealed. I call you into this world often. When I meditate, when we hold each other, when we dance; I know you come.I sense you standing there with wonder of a world that could be this loving and free, with people so complicated and flawed. It is here, in these circles, where we find love. It is here where I hear you sing.

With Love,

Sailesh